The Crossing of the Sea of Reeds marked a historic transition in the history of Israel. No longer were the Israelites subject to the land over which Pharaoh ruled. They were now God’s people, under his sole domain.

Introduction

Moreover, brethren, I do not want you to be unaware that all our fathers were under the cloud, all passed through the sea, all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, all ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank of that spiritual Rock that followed them, and that Rock was Messiah. – 1 Corinthians 10:1-4

The Crossing of the Sea of Reeds marked a historic transition in the history of Israel. No longer were the Israelites subject to the land over which Pharaoh ruled. They were now God’s people, under his sole domain. After the waters had miraculously divided, allowing God’s people to cross to safety, Moses and the Israelites sang a new song to the God Who redeemed them. With great joy they exclaimed: “מִֽי־כָמֹ֤כָה בָּֽאֵלִם֙ יְהֹוָ֔ה – “Who is like you among the gods, O LORD?” מִ֥י כָּמֹ֖כָה נֶאְדָּ֣ר בַּקֹּ֑דֶשׁ – “Who is like You, awesome in holiness?” (Ex. 15:11).

The אֵלִים (sing. אֵל) are a reference to gods in general, and in particular, to the supreme deities of the Semitic pantheon. The most notable of which was arguably Hadad or Haddu, the Canaanite and Mesopotamian storm deity of thunder and rain who was also associated with Baal Zaphon. The word baal was an honorific title given to the gods as possessors or masters of their craft. As a Semitic root, the word בַּעַל means ‘owner, lord’ (H1167) and is used in the Hebrew vernacular to refer to both humans and divine beings in correlation to their ownership or mastery of specific traits, domains, and materials. For example, a husband in Hebrew is called בַּעַל; and a בעל תשובה, lit. “master of return” describes a secular Jew who returns to faith and religious observance. In the Hebrew Bible, Joseph is described as בַּעַל הַחֲלֹמוֹת “master of dreams” (Gen. 37:19) and a בַעַל הַשׁוֹר is an owner of oxen (Ex. 21:28), etc. In technicality, Pharaoh could have easily been called בעל ישראל, “master of Israel” – in so much as he was the possessor of Jacob’s descendants.

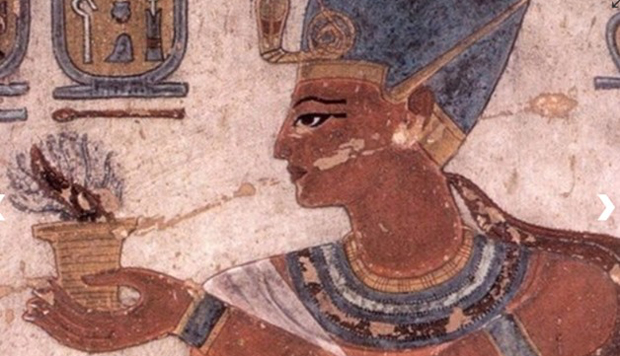

For the apostle Paul, Israel’s transition can be likened to baptism – whereby the believer is immersed in an inhabitable environment, only to emerge renewed, cleansed, and born again. The rebirth of Israel meant death to their former existence. As Pharaoh’s property, they were subject to the laws and forces that governed all aspects of Egyptian life, which included dependence on Egyptian religion. As Baines notes, “the beneficence of the gods could not be taken for granted… since in theory the gods provided for all of humanity.” Thus, Israel was subject in part to the realm of Egypt’s pantheons, and as Pharaoh’s slaves, dependent on Egypt’s wealth, economy, and resources for daily sustenance and survival. Pharaoh himself was considered divine, a manifestation of Horus in his own palace. In reality, Israel’s bondage was not only viewed as a necessity for Egypt’s highest political office, but it was likely considered to be the will of the gods themselves. The dynamic tension between Pharaoh’s lordship, the influence of Egyptian society and religion, and the sovereignty of Israel’s God is played out in the Exodus narrative of the Ten Plagues: “For I will pass through the land of Egypt on that night, and I will strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast, and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgement: I am the LORD (Ex. 12:12).”

For the Jews, the crossing of the Sea of Reeds marked not only their freedom from Egypt and her dogmatic philosophies, but it also heralded a dramatic shift in their national psyche. For nearly four and half centuries, they were denied the basic right to self-determination, and the ability to worship the God of their ancestors according to the terms He would prescribe (Ex. 8:27). Exodus chapters 15-18 describe how God tested the Israelites in the days and weeks leading up to the revelation at Mount Sinai, “in order to know what was in your heart, whether or not you would keep His commands (Deut. 8:2)”. Upon their departure from Egypt, the fledgling nation were like spiritual babes, transitioning from a slave-like mentality to becoming servants of the One True God. In the dramatic tale of the Sea of Reeds, so much more is on the line for a people learning to rely on the provision of one God above the protection of many. In so many ways, the parting of Reed Sea is the final chapter in the epic tale of how the God of Israel conquered Egypt’s gods and demonstrated His supreme authority over all elements of nature.

Pharaoh’s Resolve Strengthened

Now when Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although it was nearer; for God said, ‘The people may have a change of heart when they see war and return to Egypt. So God led the people round about, by way of the wilderness at the Sea of Reeds. Now the Israelites went up armed out of the land of Egypt. – Exodus 13:17-18

For years, scholars have sought to retrace the Israelite’s encampments in the wilderness although no archaeological evidence of their presence in Sinai Peninsula remains, and efforts to identify important landmarks relevant to their encampments has proven to be difficult. Debate continues to circulate regarding the body of water that the Bible calls the יַם־סוּף (See of Reeds) and the numerous placenames mentioned in the stations of their journeys (Num. 33:1-49). One thing is apparent in the manner in which Israel departed Egypt – they never intended to return. The indication of Pharaoh’s hasty and sudden sendoff was that the exodus was permanent (Ex. 12:31-32). As a result, the Torah mentions the quickest, easiest, and most direct route from Egypt to the Promised Land: Northeast, along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, a route that goes through Philistia (modern day Gaza). Ironically, the Torah mentions that the Israelites went up out of Egypt armed even though they had no inclination toward bloodshed. God knew that the people would lose heart when the war-mongering Philistines would perceive a mass of foreign invaders. Having left Egypt in haste, the only materials the Israelites were equipped with was the wealth of the Egyptians they had plundered in their defiant departure (Ex. 12:36).

Just as the northeastern route was the easiest way to leave Egypt, it was also the easiest way to return to Egypt. So, God led the fledgling nation through the arid and unforgiving desert; and after just three days, caused six hundred thousand fighting men, and by some estimates, three million people including women, children, and elderly adults, to circle back and encamp with their backs against the sea:

The LORD said to Moses: Tell the Israelites to turn back and encamp before Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, before Baal-zephon; you shall encamp facing it, by the sea. Pharaoh will say of the Israelites, “They are astray in the land; the wilderness has closed in on them.” Then I will stiffen Pharaoh’s heart and he will pursue them, that I may gain glory through Pharaoh and all his host; and the Egyptians shall know that I am the LORD. And they did so. (Ex. 14:1-4)

If the death of the firstborn was given as a sign for Israel (Ex. 11:7), then the Splitting of the Reed Sea was God’s culminating act of sovereignty in demonstrating His power over all facets of nature: “the Egyptians shall know that I am the LORD (Ex. 14:3).” The text reiterates on numerous occasions that God wished to demonstrate conclusively, both to Israel and to the world at large, that He was the Master of all.

The narrative leaves room for speculation that Pharaoh may have remained under the impression that Moses and the Israelites were only going for a three-day journey, as they had previously requested (Ex. 8:27-28). At any rate, even if the Israelites had no intention of returning, Pharaoh should have been so terrified by the plagues, and especially the Plague of the Firstborn, that it would have been sheer insanity for him to try to bring them back. For Pharaoh’s resolve to be strengthened, he would have to regret his error in letting the people go, and he would have to overcome the trauma of his experience with the previous plagues. Ultimately, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart through a series of ingenious maneuvers that left his reporters befuddled and stunned at what they saw: With Israel’s back against the sea, Pharaoh’s agents reported the following: They are לִפְנֵי֙ פִּ֣י הַחִירֹ֔ת – “before the mouth of freedom.” They are pinned בֵּ֥ין מִגְדֹּ֖ל וּבֵ֣ין הַיָּ֑ם – “between a tower and the sea.” And they are לִפְנֵי֙ בַּ֣עַל צְפֹ֔ן נִכְח֥וֹ – lit. “before Baal Zaphon, in front of him...” This was the only information Pharaoh needed to have his resolve strengthened, and his heart set on vindication and revenge.

What details were contained in the report that fueled Pharaoh’s resolve and gave him the courage he needed to pursue Israel? And even more puzzling: What was it about Pharaoh that frightened the Israelites after they had witnessed the superiority of their own God’s might over Egypt? At the beginning of this lengthy ordeal, Pharaoh was indignant to the challenge that rose from Israel’s corner: “Who is the LORD, that I should obey His voice to let Israel go? I do not know the LORD, nor will I let Israel go (Ex. 5:2).” It took a divine act to soften Pharaoh’s heart, and it would take an equally momentous act to strengthen it again. In retrospect, the heavenly forces that guided and protected the destiny of Egypt were no match for the God of Israel at the sea.