If the Torah prohibits human sacrifice (Deut. 12:31), then how does the righteous death of Yeshua make perfect “those who draw near to worship?" (Heb. 10:1).

Introduction: Premise for Atonement

At the head of creation, God brought the universe into existence through the agent of his powerful word.[1] God’s primordial work was perfect, wholly righteous, and very good.[2] Through the transmission of communicable attributes[3], the first humans were elevated to prominence in creation, given the task of managing God’s creative work through resourcefulness, and influencing the whole of creation to maintain harmonious union with the Creator. However, when Adam sinned, mankind fell from his spiritual ascendancy. Thus, the thrust of the Biblical narrative henceforth is the restoration of creation, namely humanity, to the harmonious relationship it had before sin entered the world.

The Hebrew word for sin, חתא [chet], literally means a lack. In essence, the act of sin itself diminishes the sinner. God’s means for rectifying Adam’s sin and reconciling all sinners to himself is atonement. In his article for the New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, R.W. Yarbrough writes concerning the function of atonement: “It is the divine activity that confronts and resolves the problem of human sin so that people may enjoy full fellowship with God both now and in the age to come.”[4] Essential to Yarbrough’s definition of atonement is the idea that atonement is purely a “divine act.” Humans, as the deficient party, cannot make atonement for themselves. Therefore, it must be God who sets the parameters for the means of reestablishing relationship and cosmic order.[5] Essential to mankind, is the responsibility to recognize sin for what it is and to turn towards God in repentance. God, in his attribute of mercy, enables him to do so.

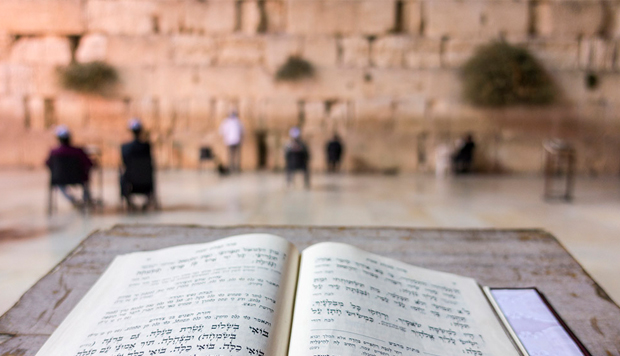

In the Old Testament, the theme of atonement is centered on the sacrificial system. The Hebrew word for sacrifice, קרבן [korban], literally denotes nearness. Far from the impression of a blood thirsty deity desirous of appeasement, ‘korban’ expresses the opportunity that God extends to his people to willingly draw near in proximity and relationship. It is important to note that although a major function of the Temple was to accomplish atonement, most of the offerings had little to do with atonement.[6] Nevertheless, the theme of atonement found its apex in the annual Day of Atonement.

In the New Testament, the theme of atonement finds its centrality in the death of Yeshua the Messiah. As the apostle writes: “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree (1 Pet. 2:24 NKJV).” It is evident that the Bible communicates a progressive development concerning the agents of atonement. At the heart of the issue is the conceptual transition from animal sacrifice to the atoning work of Yeshua. In that regard, a conflict of continuity arises in deference to the Torah’s explicit prohibition against human sacrifice (Deut. 12:31). Hence, a critical question must be asked concerning Yeshua: If the Torah prescribes animal sacrifice for atonement, then how does the righteous death of Yeshua make perfect “those who draw near to worship? (Heb. 10:1).”

In view of the unfolding biblical history of redemption, it is necessary to examine key Biblical passages that clearly articulate continuity across the spectrum of Scripture. In this study, we will narrow our examination to four Biblical passages: Leviticus 17:11; Numbers 19:1-20:2; Hebrews 9:1-15; and Revelation 5:9-10. As we examine these key passages, we will consider their context and, in some cases, evaluate their most ancient interpretations in light of their messianic implications. Thus, establishing a critical framework as we follow the redemptive narrative.

Leviticus 17:11: What About the Blood?

One of the most recognizable consequences of human sin is death. The Bible makes this explicitly clear when Adam partakes of the tree of life: “For in that day that you eat of it you shall surely die (Gen. 2:17).” There are numerous consequences of human sin, among them is that death entered the world (Rm. 5:12). The contributing factor to mankind’s severance with God is the inability of finite mortals to withstand the consuming presence of the infinite God (Ex. 33:20). According to the apostles, the most obvious remedy for death is life itself: “For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Yeshua the Messiah our Lord (Rom. 6:23)”

According to Scripture, the quintessential agent of atonement is blood: “For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it to you upon the altar to make atonement for your souls; for it is the blood that makes atonement for the soul (Leviticus 17:11).” Once again, it is essential to note that God doesn’t desire blood per se, however, because blood is the life-giving force that invigorates all creatures, blood represents life; and therefore, qualifies as an appropriate agent of atonement. The Encyclopedia Judaica explains: “Sin and defilement damage the relationship between creature and Creator, and the process of atonement – through repentance and reparation – restores this relationship.”[7]

In terms of atoning sacrifice, it is understood that the blood of an unblemished animal, i.e. an innocent life, serves as an expiation on behalf of the diminished soul, i.e. those affected by sin. This concept is represented in the Hebrew term for atonement, “kippurim” from the verb “kafar.” Although this word is generally translated as “atonement”, the literal meaning is ‘covering.’ On that note, the foremost commentator in the Jewish world, Rashi,[8] expounded on the implication of blood as an agent for atonement: “God designated blood as the medium that goes upon the altar for atonement, as if to say, ‘Let one life be offered to cover for another.’”[9]

In practical terms of application, there are three primary services in which blood accomplished atonement: The inauguration of the Divine Service (Lev. Ch. 9); the annual Day of Atonement (Lev. Ch. 16); and individual offerings brought for inadvertent transgressions (Lev. 4:27; 5:14). Through a brief synopsis of these services, the Biblical theologian is able to deduce the essential elements for establishing the ground rules in anticipation of the atoning death of Yeshua.

In the days of the Temple, the centerpiece for understanding atonement was Yom Kippur – The Day of Atonement – literally, the “Day of Coverings”. Many of its components were performed at no other time of the year and the day’s service was almost exclusively performed by the High Priest. In terms of its unique status, it still holds a special place in Judaism as the holiest day of the year.[10] The day itself involved the intersection of three spheres of holiness: On the holiest day of the year, the holiest man in the world (High Priest), would go into the holiest place on earth (Holy of Holies) and act as an emissary on behalf of the entire nation. Like the day of his inauguration service, Aaron and subsequent High Priests were required to offer an atonement for themselves and for the nation. As God’s emissary, it was necessary for the High Priest to offer his sacrifice first. The Talmud relates the importance of sequence: “One could not atone for others unless he himself was free from sin.”[11] As we shall see, this concept will prove to be an essential principle in establishing the eligibility of Yeshua to expiate and propitiate sin.

After the High Priest made atonement for himself through the offering of a young bull, he would make atonement on behalf of the nation through the lottery selection of two goats (Lev. 16:7-11). The blood of the bull and the goat selected for God would then be applied to the ark and all of the holy vessels in the sanctuary. The idea was that over the course of the year, the Temple itself became ritually unfit as people trudged in and out with their contamination and sin. Because the holy vessels ministered perpetually before the divine presence, they too needed a covering. Without the purification ritual of Yom Kippur, God would be forced to withdraw His presence from the sanctuary entirely.

A final aspect that is often overlooked is the role of God’s people on the Day of Atonement. Among the most distinguishing features of the day was the obligation of the people to fast, pray, and engage in repentance and introspection: “It is the Day of Atonement, when atonement is made for you before the Lord your God… you must deny yourselves (Lev. 23:26-32).” Such details are important to note as additional principles are derived from them: The Day of Atonement required an elevated awareness on the part of the people. Those who regarded the Day of Atonement as merely a day of refraining from work and food without a spiritual dimension, did not find atonement on that day. Thus, it was essential to recognize the day as holy and treat it as such (ibid. 23:29). Similar to the principle found in Sin offerings brought by individuals throughout the year,[12] a person could not treat God’s holiness casually or continually sin with a high-hand and expect Yom Kippur to cover it. Atonement necessitated contrite repentance and a change of the attitudes that made it possible for transgressors to flout God’s will. This understanding serves as a critical prelude for the role of atonement in the New Testament, and the responsibility of believer’s upon accepting it (Heb. 10:26-29).

In review of the primary agent of atonement, blood sets forth key principles: First, Atonement is God’s remedy for death through an agent of life; second, the emissary acting on behalf of Israel had to be without sin before he could atone for others; and thirdly, atonement necessitated a response, namely, acceptance of God’s sovereignty and provision through repentance.

Numbers 19:1-20:2: The Atonement of the Righteous

As we move forward in the unfolding story of redemption, the Bible introduces one of the more baffling passages in all of Scripture, the Ashes of the Red Heifer:

[2-3] Speak to the children of Israel, that they bring you a red heifer without blemish, in which there is no defect and on which a yoke has never come… take it outside the camp, and it shall be slaughtered… [6] And the priest shall take cedar wood and hyssop and scarlet, and cast them into the midst of the fire burning the heifer… [9] [he] shall gather up the ashes of the heifer, and store them outside the camp in a clean place; and they shall be kept for the congregation of the children of Israel for the water of purification; it is for purifying from sin… [20:1] And Miriam died there. (Numbers 19:1-20:2)

If one is to interpret the Torah’s chronology literally, then it would appear that nearly thirty-eight years separate the revelation of the commands concerning Yom Kippur and the Ashes of the Red Heifer. However, this view is heavenly contended. Nevertheless, the placement of these passages, particularly the latter, in view of the Biblical narrative is quite revealing.

According to the Torah, an alternative agent of atonement was required for individuals and families who had become defiled through contact with a human corpse (Num. 19:16). The process entailed one of the most bizarre procedures in all of Scripture. First, a red cow, blemish-free, is slaughtered outside the Temple confines and burned together with cedar wood, hyssop, and crimson thread – items that allude to vicarious atonement, repentance, and humility (cf. Lev. 14:4-7).[13] The second act involved the retrieval of fresh water from a spring or river with a pure vessel. Then, the ashes of the heifer were poured into the vessel and mixed together. Finally, a pure person would throw the ash-water upon a contaminated person on the third and seventh days of their cleansing. Thus, contributing to the restoration of the affected person’s eligibility in regard to corporal participation in the Temple service.

It is almost incomprehensible how the ashes of a heifer, sprinkled on those contaminated, can rectify sin.[14] In fact, the Talmudic Sages were at a loss to describe this passage and explained that these laws are beyond human comprehension; a mystery reserved for the revelation of Messiah. [15] A curious phenomenon is that the ashes of the red heifer both purified the contaminated persons and defiled the emissaries who performed its service (Num. 19:7-12); a similar dynamic is attested in the role of Yeshua (Jn. 9:39). As baffling as it may be, it is self-evident that since all of Scripture is “God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16-17), any inability to comprehend a given passage reflects the limits of human capacity, not God. Interestingly, since ancient times, the laws of the red heifer have been interpreted in view of their proximity to passages concerning the death of righteous people: “Miriam died there and was buried there. Now there was no water for the congregation (Num. 20:1-2).”[16]

Given the proximity of Miriam’s death to the order of the red heifer, an important principle was deduced by the ancient scholars concerning the death of the righteous:

“Rabbi Ami said: ‘Why was the verse that describes the death of Miriam juxtaposed to the portion dealing with the red heifer? To tell you: ‘Just as the red heifer atones for sin, so too, the death of the righteous atones for sin.’”[17]

In view of the progressive nature of special revelation, it is accepted that indeed, the Torah makes provision for the atoning death of the righteous apart from the atrocity of human sacrifice. In this regard, it is not inconceivable that the merits of righteous individuals could be extended to cover a multitude of sinners.[18] Furthermore, it isn’t unreasonable to assume that the Torah alludes to an agent of the highest merit. It is on this premise that the prophet Isaiah wrote concerning the anticipation of such an individual: “But He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities; The chastisement for our peace was upon Him, And by His stripes we are healed (Isa. 53:5).” When this principle is properly discerned, it becomes apparent that Moses was inspired to juxtapose nearly every major passage concerning atonement with the sanctifying death of the righteous.[19]

Numbers 9:1-15: Eternal Redemption

By the beginning of the First Century CE, the notion that God would accept the death of the righteous as an agent of atonement was well-established in Judaism. In particular, it was understood that one such individual was worthy to bare Israel’s burden in every generation.[20] However, the focus of that expectation was tied to the anticipation of a messianic figure who was merely human. The New Testament does not portray Yeshua as such. As R. W. Yarbrough notes, “[If] Yeshua was no more than human… why should his death, even granting that he intended it somehow to be for others, be any more significant than the deaths of other people for their fellow humans?”[21]

Following the pattern established in the Torah concerning the death of the righteous, it is necessary to consider the extent to which the death of an immaculate individual would affect atonement and contribute to the merit of those who accept him. In the simplest definition of terms, the Bible consistently defines a righteous person as one who accepts the sovereignty of God and is obedient to his commandments. For example, Noah was considered righteous in his generation for having done everything God commanded (Gen. 6:9, 22); Abraham was considered righteous for his faith (Gen. 15:6); and so too, Zechariah and Elizabeth, and many others, were considered righteous before God (Lk. 1:6). Yet, all of these individuals were also anticipating the ultimate redemption in their imperfect state (Heb. 11:16). Thus, the writer of Hebrews writes concerning the transcendent nature of Yeshua’ merit :

For if the blood of bulls and goats and the ashes of a heifer, sprinkling the unclean, sanctifies for the purifying of the flesh, how much more shall the blood of Messiah, who through the eternal Spirit offered Himself without spot to God, cleanse your conscience from dead works to serve the living God? (Hebrews 9:13-15)

The righteousness of Yeshua was to the degree that he lived a life devoid of sin: “For He made Him who knew no sin to be sin for us, that we might become the righteousness of God in Him (2 Cor. 5:21).” For the writer of Hebrews, Yeshua’ death was not only superior to the blood of goats and bulls offered on Yom Kippur, and the ashes of the Red Heifer, but his blood was sufficient to provide atonement for all generations, past, present, and future; and not only for Israel but for the entire world! Thus, the merits of Yeshua are completely transcendent. Prior to highlighting the foremost agents of atonement, the author demonstrates the many ways in which the atonement procured by Yeshua is better:

“Messiah came as High Priest of the good things to come, with the greater and more perfect tabernacle not made with hands, that is, not of this creation. Not with the blood of goats and calves, but with His own blood He entered the Most Holy Place once for all, having obtained eternal redemption. (Hebrews 9:11-12)

Having established a premise in the Torah concerning the death of the righteous, the writer of Hebrews expounds on the concept[22] to explain that the apex of such expectations is the agency of the divine and perfect Messiah. Through the expiation of his righteous death, and through his demonstrated power in the resurrection, Yeshua of Nazareth transcends ordinary righteousness. He serves in a greater and more perfect Temple, one that is not merely a copy of what is in heaven,[23] but the original design. Yeshua’ priesthood is not of the created order – having entered into the “Most Holy Place” once and for all.

Moreover, Yeshua’ propitiation was much better – “not with the blood of goats and calves” – but with his own blood. The author’s logic is such: If the soul [nefesh] of an animal without blemish is an appropriate agent of atonement, how much more so the blood of the transcendent Messiah, who laid down his life through the eternal Spirit [Ruach].[24] Clearly, the quality of Yeshua’ atonement is completely transcendent. Thus, the author provides an exclamation to his statement: “[He] having obtained eternal redemption (Heb. 9:12).”

Revelation 5:9-10: Hope of What is to Come

As we shift focus to our final witness, it is essential to summarize the theological implications of atonement in the New Testament. It is axiomatic that Yeshua’ death is repeatedly presented as the apex of what the offerings of atonement anticipated in the Torah. As we have established, the original premise for atonement was for the reconciliation of mankind back to its Creator. This reconciliation is portrayed in the Gospels and Epistles as being accomplished in Yeshua: “In Messiah, God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation (2 Cor. 5:19).”

What then is to be said of the relevance of atonement in Messiahian theology and ministry? The answer to that question can be derived in response to the hope that awaits mankind at the final and ultimate redemption:

And they sang a new song, saying: “You are worthy to take the scroll, and to open its seals; for You were slain, and have redeemed us to God by Your blood out of every tribe and tongue and people and nation, and have made us kings and priests to our God; and we shall reign on the earth (Revelation 5:9-10).”

In view of the atoning death of Yeshua, it is critical to understand that the principles that applied to the offerings also apply to the New Covenant: Just as Yom Kippur only atoned for people who recognized the day as holy and treated it as such (Lev. 23:29); so too, only those who honor the righteousness of Yeshua in this life benefit from his heavenly ascent. The writer of Hebrew adds: “How much more severely do you think someone deserves to be punished who has trampled the Son of God underfoot, who has treated as an unholy thing the blood of the covenant that sanctified them, and who has insulted the Spirit of grace? (Heb. 10:29).” The implication of atonement is such that the atoning sacrifice of Yeshua necessitates a response on the part of God’s people. On that note, the Apostle Paul reminds his audience: “You were bought at a price; therefore, glorify God in your body and in your spirit, which are God’s (1 Cor. 6:20).

On that point, it is appropriate to revisit the condition that precipitated the need for atonement in the first place: Because of man’s sin, death entered the world, effectively severing the relationship between God and humanity as it was at creation. The issue at hand is the rectification of the divine image in Adam (Rm. 5:12-21). Yeshua is demonstrated to be the kapara (the covering) of human sin – the “righteous for the unrighteous” (1 Pet. 3:18). The New Testament speaks of this defining act as the expiation for life; most vividly played out in the shedding of Yeshua’ blood: “For it pleased God that in Him all the fullness should dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross (Col. 1:20).” And again, he writes: “Even when we were dead in transgressions, [he] made us alive together with Messiah (Eph. 2:4-10).” Thus, in view of the unfolding history of redemption, the depth and width of God’s solution for human sin finds its perfection in the person of Yeshua the Messiah.

Alas, all the ingredients are in order for reflection on our final passage (Rev. 5:9-10). As John lived out his last days in exile, he envisioned the tangible reality that await those who put their trust and assurance in the redeeming work of Yeshua. The writer of Hebrews also assures us of this reunion: “Messiah, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him (Heb. 9:28).” Thanks to the unlimited merit of Yeshua, the hope of redemption is available to every tribe, tongue, people, and nation. All of creation groans as we eagerly await the redemption of our souls (Rm. 8:24). Having been redeemed by the blood of Messiah, we do not consider trivial the responsibility that comes with this awareness. As we look forward to the Messiah’s second coming, we remain active “priests on earth” seeking to inspire mankind in anticipation for the renewed harmony of creation.

[1] Psalm 33:6; John 1:1-3; Hebrews 1:3.

[2] Genesis 1:31.

[3] Genesis 1:26-28.

[4] R. W. Yarbrough, “Atonement” in New Dictionary of Biblical Theology (Downers Grove, IL.: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 388.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The Torah provides five categories of individual offerings in addition to the daily communal offerings (Lev. Ch. 1-6). Most offerings were brought willingly for the purpose of drawing near in devotion, unity, and thanksgiving. Nearly all the offerings were consumed by the priests facilitating the service or the individuals and families bringing the offerings.

[7] Atran, Frank Z. “Atonement.” In Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 3, 830.

[8] Acronym for Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (1040-1105), known for his comprehensive commentaries on the Bible and Talmud.

[9] Rashi to Leviticus 17:11.

[10] Holiness, kadosh, is distinguished as ‘separate’. Yom Kippur is a day unlike any other.

[11] Babylonian Talmud. Bava Metzia 107b.

[12] According to the Torah, there is no provision of atonement for intentional sin (Lev. 4:27; 5:14).

[13] Cedar wood. Because it grows tall, symbolizes haughtiness (Rashi; Arachin 16a). Hyssop. A lowly bush, symbolized new found humility (Rashi). Crimson. Carries symbolic imagery of atonement and humility.

[14] Cf. Hebrews 9:13

[15] Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 35a.

[16] Miriam’s death precipitates the absence of water. Since ancient times, it was understood that the rock that accompanied Israel in the wilderness was given in Miriam’s merit. The Aramaic Targum renders the verse: “Miriam died there… and because of Miriam’s merit the rock was given, when she died the water was hidden (Targum Jonathan, Num. 20:1-2).” Thus, Miriam’s death served to illustrate the anticipation that the death of the righteousness could atone for sin.

[17] Babylonian Talmud, Moed Katan 28a.

[18] C.f. Genesis 18:16-33.

[19] The death of Aaron’s sons, Nadav and Avihu, were justified as a means of sanctifying God’s name before the people (Lev. 10:3). Their deaths are the catalyst for the Yom Kippur service (Lev. 16:1). The Jerusalem Talmud also regards their death as an indicator of the principle: “Just as Yom Kippur brings atonement, so the death of the righteous brings atonement.” (Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 1:1).

[20] In Judaism, and more specifically within the Hasidic movement, the notion exists that in every generation there is a person who is worthy to be Messiah.

[21] R. W. Yarbrough, “Atonement” in New Dictionary of Biblical Theology (Downers Grove, IL.: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 392.

[22] C.f. Hebrews 12:24 – It is evident that the author of Hebrews understood the innocent death of Abel as extending merit to that generation, albeit the blood of Yeshua is superior than the blood of Abel.

[23] Hebrews 8:5; 9:24; 10:1.

[24] Cf. Leviticus 17:11 – We refer back to our initial passage: “The Soul [nefesh] of a creature is in the blood.” Nefesh is the life force shared by all creatures, human and animals. Mankind is unique, possessing an eternal life force that is gifted by God i.e. Ruach (wind/spirit) and Neshama (Breath).