Since the earliest times, geography has played a significant role in shaping the course of human history. For this reason, geography is paramount to understanding the Torah.

At the heart of covenant theology is the intersection of three spheres of holiness: God’s relationship with the Jewish people, God’s relationship with the Promised Land, and Israel’s relationship with both. From the snow-covered mountains of Lebanon in the north, to the arid Negev in the south, and extending eastward through the vast Syrian-Arabian desert, these are the natural borders of the land of the Bible. Within their boundaries, God enacted the unfolding history of redemption: “The Lord said to Abram… Lift your eyes now and look from the place where you are – northward, southward, eastward, and westward; for all the land which you see I give to you and your descendants forever” (Gen. 13:14-15).

Since the earliest times, geography has played a significant role in shaping the course of human history. Geography directs where people migrate, populations congregate, and where geopolitical boundaries and civilizations are established. For this reason, geography is paramount to understanding the Torah. As Andrew Hill & John Walton explain: “The Bible is not a portal into an artificial and contrived Narnia-like literary history."[1] On the contrary, the Bible records real events taking place within time and space; and as such, God chose a strategic location from which his revelation and plan for humanity would emanate: “For out of Zion shall go forth the Law, and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem” (Isa. 2:3).

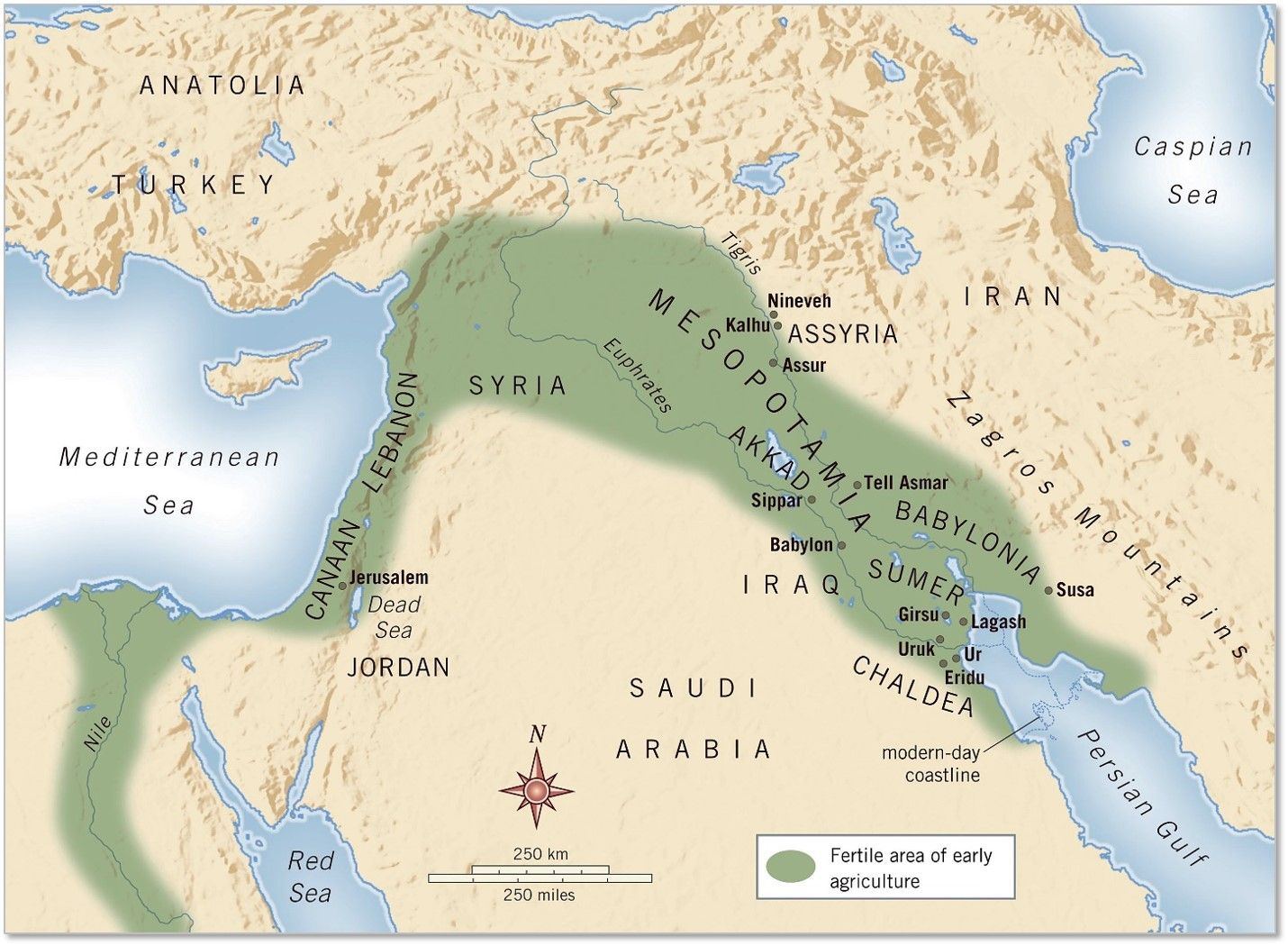

Fertile Crescent

The decisive geological factor in God’s selection of the Promised Land is, “its outermost position at the southwest end of the settled fertile lands of the Near East.”[2] Often referred to as the ‘cradle of civilization’ for its place in cultivating advances in agriculture and innovation, these lands are surrounded by the overarching ‘Fertile Crescent’ – a bow shaped region known for its fertility and abundance of water. With the two great rivers, Tigris and Euphrates, running southeasterly at the northern most extremity,[3] and the merchant Mediterranean Sea to the west, the topographic sphere known as the Levant was the perfect place for civilizations to intersect. Today, the Levant comprises of Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and present-day Turkey southeast of the Euphrates.[4]

Serving as a natural land bridge connecting three continents, Africa, Europe, and Asia; the Levant, and specifically the land of Canaan, was the ideal place to generate exposure in the ancient world. Amid the constant influx of international travelers that utilized the region’s strategic highways for trade and commerce, the nations would encounter a people and a God unlike any other:

Surely I have taught you statutes and judgments… that you should act according to them in the land which you go to possess… for this is your wisdom and your understanding in the site of these peoples who will hear… and say, ‘surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.’ (Deut. 4:5-8).

By bringing Abraham to the land of Canaan and promising him that the land would become the heritage of his offspring, God was establishing the land as the eternal inheritance of the Jewish people; a special place where Israel would sanctify God’s name as kingdom of priests and a holy nation.[5] However, functioning as God’s ‘emissaries’ to the nations would not be easy; after all, Abraham’s descendants were to be in the vanguard of perfecting the world by observing the Torah, building the Temple, and bringing about King Messiah as a light to the nations (Isa. 49:6). With such a great honor comes great responsibility, and life in the land demanded a level of sanctity unparalleled in the secular world. As biblical scholar and geographer, Dr. Barry Beitzal, explains: “Jewish faith in the Torah was inextricably tied to space, and ‘land’ became the prism of this faith. Land/space was an arena in which God acted mightily on behalf of his people” (Beitzel 2009, 16).[6]

The Promised Land

According the Bible, the Promised Land itself was said to extend from the wadi of Egypt to the Euphrates in the north (Gen. 15:18; Josh. 1:4). However, it is apparent from the geopolitical history of the region that Israel’s geographic borders never reached that extent. Needless to say, God’s promise did not necessarily indicate that Abraham’s descendants would always possess the land, as history would show that during the long periods of exile they certainly did not. Rather, the thrust of God’s promise was that the nation of Israel and the land of Israel would always be destined for each other. This is most evident in the numerous eschatological passages where the Torah prophets speak of the returning exiles (Zech. 14:7-9); coupled with the fact that Abraham never took legal possession of the land in his lifetime (Heb. 11:8-13).

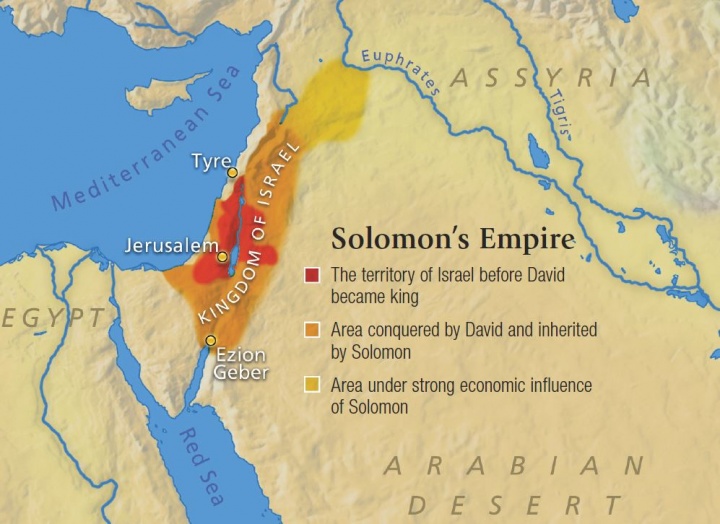

The United Kingdom

Israel’s initial borders upon conquest and allotment are described in the book of Joshua (Ch. 13-22). However, the ascendancy of Israel’s geopolitical sovereignty was realized during the Davidic monarchy under the rule of King Solomon: “And Solomon ruled over all the kingdoms from the Euphrates River to the land of the Philistines, as far as the border of Egypt” (1 Kings 4:21). Solomon was the most powerful monarch of his time. The surrounding kings feared him, paid him homage, and supplied him with vast amounts of resources. However, after the split of the northern and southern kingdoms, and especially after the Babylonian/Persian exile and subsequent wars and Greco-Roman conquests, the Land was subdivided into multiple geopolitical districts.[7]

The Biblical heartland was and still is the hilly region stretching north to south from the lower Galilee to the Dead Sea and extending east to west from the Jordan river to the plains of Sharon. Also known as Cisjordan (west side of the Jordan river), the region is designated by its ancient names, Judea and Samaria. Within this region Abraham first received the promise (Gen. 12:7) and purchased a burial site for Sarah from the Hittites at the Cave of Machpelah (Gen. 23:1-20).[8] However, surrounding this hallowed heritage were local nations that sought to lure Israel’s from her covenant obligation.

To the southwest along the coast near present-day Gaza and Ashkelon were the Philistines. At Israel’s front to the east beyond the Jordan River was Edom, Moab, Gilead, Bashan, and Mishor. These five nations inhabited what known in modern geographical terms as the Transjordan. It is worth noting that at one time in Israel’s early history, much of the Transjordan region fell under Jewish sovereignty as part of the allotments belonging to the tribes of Gad, Reuben, and the half tribe of Manasseh. However, because of its proximity to Moab, and the natural land barrier presented by the Jordan river, frequent conflict and internal division made it difficult for Israel to have any shot at maintaining long-term sovereignty there. Nevertheless, throughout biblical history, the Cisjordan was notable for its majority Jewish population; and was most distinguished for possessing the seat of religious and political authority in Jerusalem. Three times a year, hundreds of thousands of Jewish pilgrims from all over the world ascend to Jerusalem in order to celebrate the three pilgrim holidays of Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot (Ex. 34:23; Deut. 16:16).[9]

A Land of Faith & Blessing

For many modern readers, it is difficult to conceptualize the significance of Israel’s geography and the impact it has on the Biblical narrative. However, some of the Bible’s most critical lessons on faith and trusting obedience are only attainable through an understanding of the land’s topographical and meteorological implications. Most axiomatic is the region’s dependency on rain: “But the land you are crossing the Jordan to take possession of is a land of mountains and valleys that drinks rain from heaven. It is a land the LORD your God cares for; the eyes of the LORD your God are continually on it from the beginning of the year to its end” (Deut. 11:11-12 NIV).

For all of its abundance and goodness (Ex. 3:8, 17), God’s promised land was not like the Land of Egypt, which was watered by the fertile Nile River (Gen. 13:10). Rather, ‘from the rain of heaven will it drink its water.’ This is just as true today as it was in ancient times. As the Macmillan atlas notes, “in several instances, the major distinct regions of the land are clearly defined and listed in the Bible according to topography and climate” (Aharoni & Avi-Yonah 1993, 14).[10] According to the Bible, the seasons can be categorically divided into two: summer and winter. These seasons are bookended by the Biblical holidays that arrive in the fall and spring.[11] In modern times, Israel’s annual precipitation is around 550 mm (21.5 in).[12] Subsequently, all of the year’s rainfall is concentrated during the winter months (mid-November to early-March). Furthermore, it is essential that whatever rain falls during that time is preserved throughout the year.

The implications of rain in terms of national prosperity are far reaching. The Galilee region in the north possesses the largest freshwater lake in the Middle East.[13] Although Lake Galilee is fed by the Spring of Banais and the Jordan river, which also flows into the Dead Sea, the water levels of the lake are significantly impacted by annual precipitation. In ancient times and to an extent even today, precipitation yields could make or break a society. As an agricultural society, Israel was absolutely dependent on rain. In view of its location between the Transjordan desert and the Mediterranean Sea, the nation’s weather was significantly influenced by both.

The most critical season for Israel’s harvest corresponded to the months of April/May on the Gregorian calendar.[14] The westerly winds brought life giving rains from the sea, whereas the easterly winds brought the dryness of the desert. During these crucial months, the weather in Israel changes drastically as the westerly winds change course and give to the arid winds of the east. Within a matter of days, if not hours, the weather can increase by 15-20 degrees Fahrenheit; allowing pollination to take place. However, if the weather suddenly reverts during the transition period, rain at the wrong time could prove catastrophic for Israel’s produce. Such context sheds light on God’s assurances with regard to national prosperity in correspondence with Israel’s covenant faithfulness:

So if you faithfully obey the commands I am giving you today – to love the LORD your God and to serve him with all your heart and with all your soul – then I will send rain on your land in its season, both autumn and spring rains, so that you may gather in your grain, new wine and olive oil (Deut. 11:13-14).

On this topic, the Talmud elucidates:

God continuously observes the Land of Israel and its people to see how to allot the rain and other natural benefits. If much rain was ordained but the people become unworthy, God may make the rain fall at the wrong time or in the wrong places. Conversely, even if the original allotment was small, but the people repented, God can make every drop fall to maximum advantage (Rosh Hashanah 17b).

Such is the nature concerning God’s relationship with Israel, and Israel’s relationship to the land. Moses was correct in asserting the utter distinctness of the Land of the Bible. For this reason, the Land itself is intrinsically holy, separate (kadosh), set apart. No other land demanded perpetual reliance on God’s blessings to saturate it. And no other land could be said to inherently regurgitate perpetual depravity (Lev. 18:25). In regard to its yield, there was nothing the Israelite farmer could do but to rely on God with perfect faith. This was one of the more critical lessons of life in the Holy Land. The Jewish farmer was compelled to be mindful through his heartfelt expression of gratitude that every accomplishment, no matter how much sweat and effort he invested, was ultimately a gift from God, and could not have been received had it not been for God’s continued providence and compassionate guidance throughout his history.

[1] Hill, Andrew E., Walton, John H., A Survey of the Torah (Grand Rapids, M.I.: Zondervan, 2009), 35.

[2] Aharoni, Yohanan, Avi-Yonah, Michael, The Macmillan Bible Atlas (New York, N.Y.: Carta, 1993), 12.

[3] Greek ‘Mesopotamia’ (Between the two rivers).

[4] The Euphrates is referred to in the Bible as ‘The Great River’ (Genesis 15:18).

[5] Exodus 19:6; Isaiah 61:6; 1 Peter 2:9; Revelation 1:6.

[6] Barry L. Beitzel, The Moody Atlas of the Bible (Oxford, England: Lion Hudson PLC, 2009), 16.

[7] These districts generally fall under two categories: Cisjordan (west side of the Jordan river) and Transjordan (across [the east side] of the Jordan River).

[8] Later to be known as Hebron (Joshua 21:11).

[9] Hebrew: Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot.

[10] Cf. Deuteronomy 1:7; Joshua 10:40; 11:16; Judges 1:9.

[11] See Leviticus Ch. 23.

[12] Kat, J. “Rain.” In Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House, Ltd., 1971), vol. 3, 1522.

[13] The lake goes by several names, biblically and historically: Lake Tiberias, Kinneret, and the Sea of Galilee.

[14] The second month on the Jewish calendar (Late Nissan to early Sivan); also corresponding to the 49 days between Passover and Pentecost (Sefirat Ha’Omer).